Calab Rare Books

Antonius à BURGUNDIA

Antonius à BURGUNDIA

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

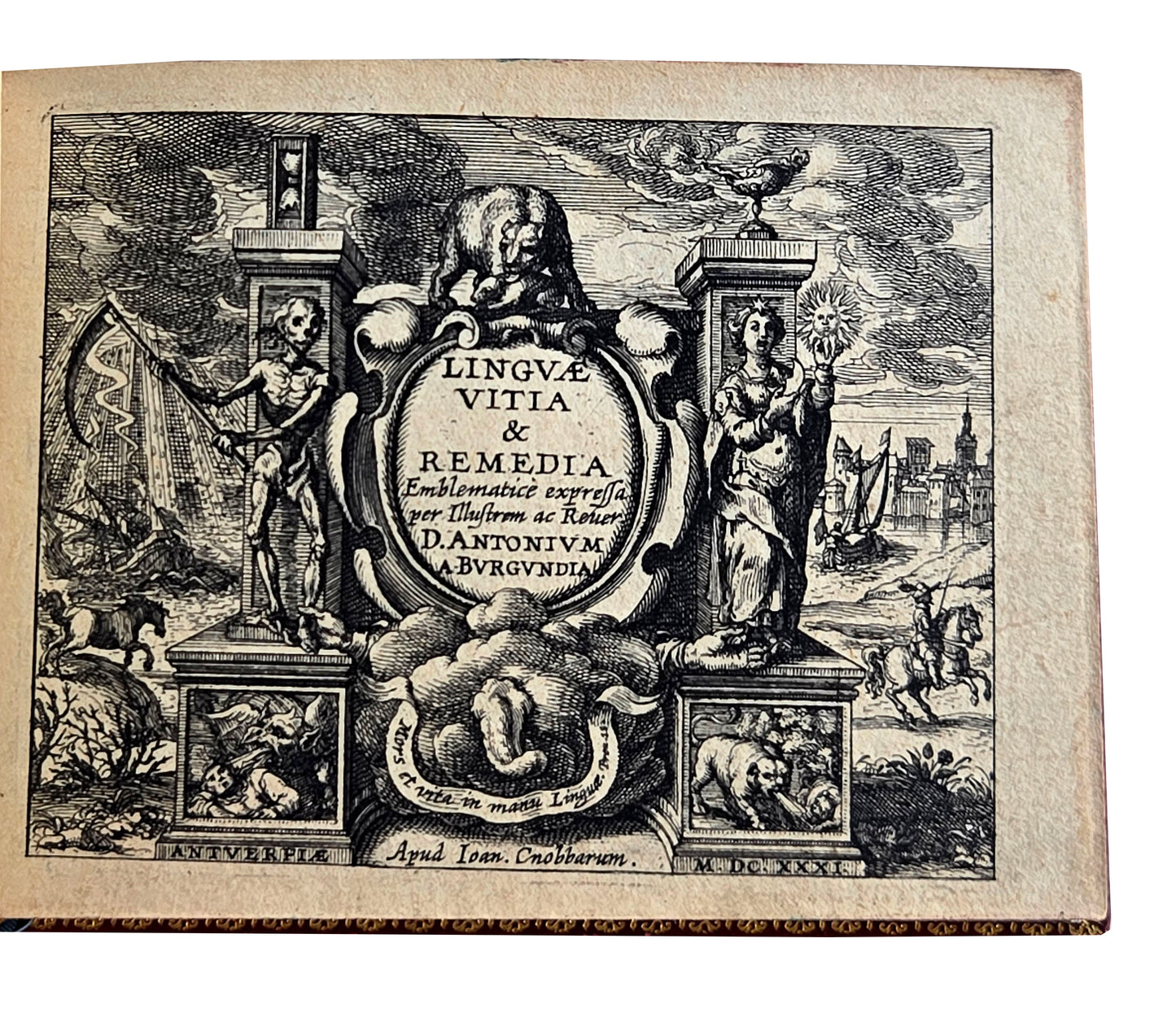

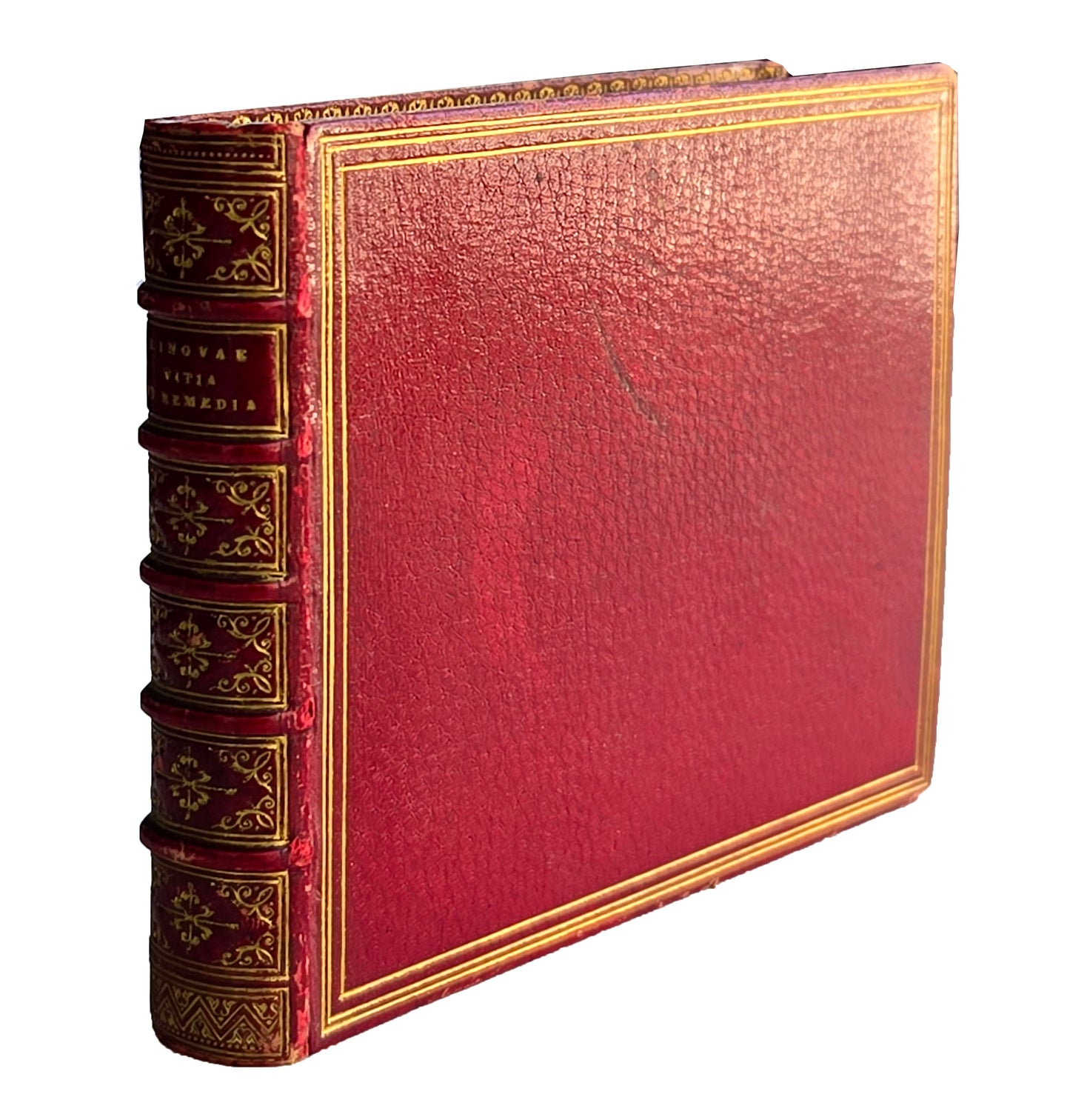

Linguae vitia et remedia. Emblematice expressa. [24], 192 pp. Illustrated with a finely engraved emblematic title, 4 full-page general emblematic engravings, and 90 finely designed full-page emblems, 45 for the defects of speech, and 45 for the remedies, engraved by J. Neefs and A. Pauwels after Abraham van Diepenbeek. Oblong 32mo., 70 x 92 mm, bound in full red morocco by Trautz-Bauzonnet. Antwerp: Ioan. Cnobbaert, 1631.

Rare First Edition of this extraordinary pedagogical emblem book, remarkable in that the text and images were directly inspired by Erasmus' 1525 dissertation on "Lingue" (i.e. tongue) which aimed to expose the vices of speech that were so blatantly displayed by his contemporaries (specifically by self-important theologians and complacent friars). T. van Houdt has shown convincingly that a significant number of picturae chosen by Antonius à Burgundia to illustrate the various vices of the tongue were derived directly from anecdotes and comparisons found in Erasmus' diatribe.

The motives for the present emblem book were similarly humanistic: to instruct lay people (especially children) on the proper use of speech; and furthermore, to make all people "more humane" (the goal of humanism). "In doing so, Antonius elegantly reveals the formative and educational purposes of the book, while at the same time acknowledging in an equally charming, albeit less obvious, manner his indebtedness to the great humanist and pedagogue, Desiderius Erasmus" (van Houdt).

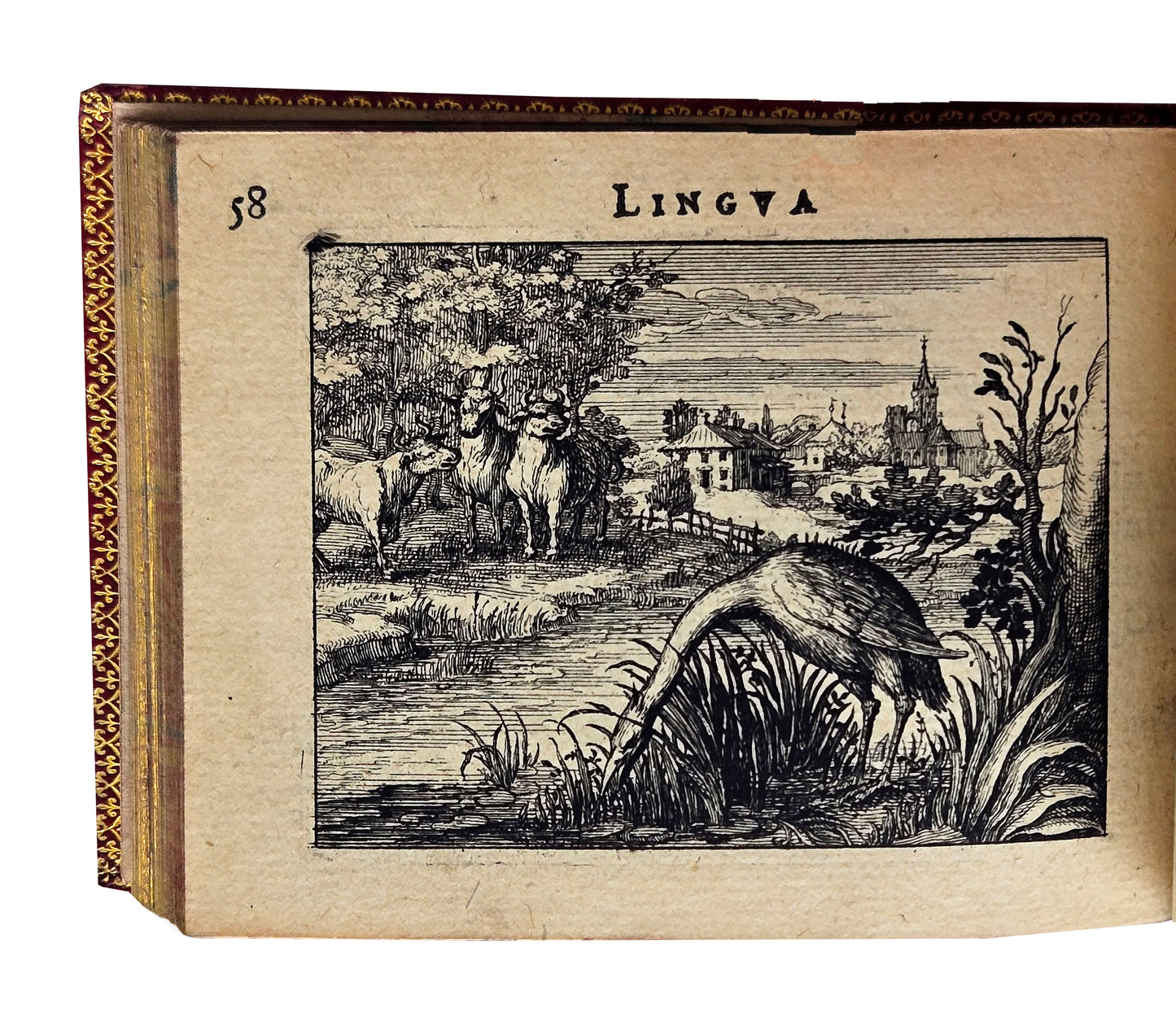

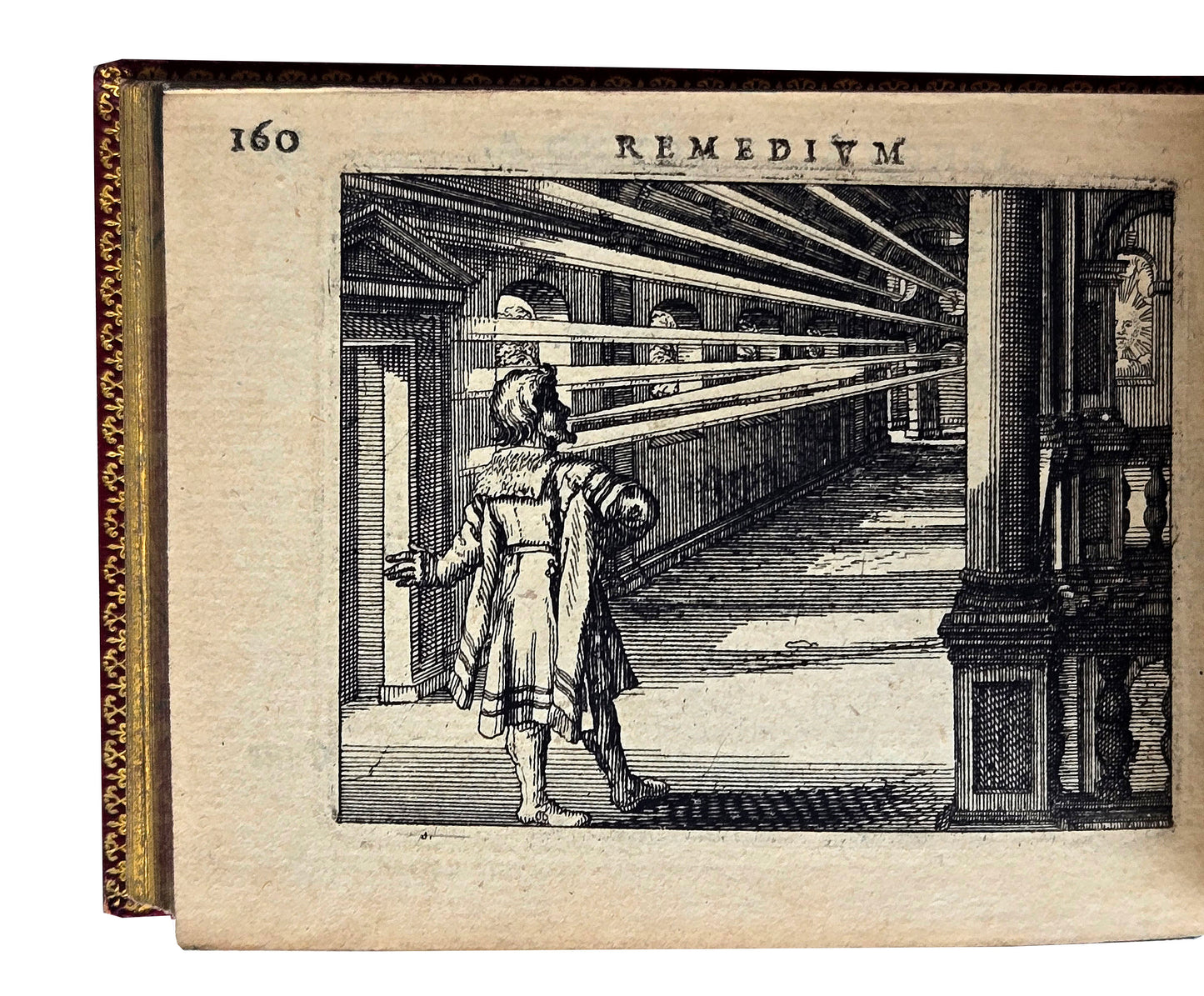

The emblems are divided into two series of forty-five emblems each: the first series concerns the shortcomings of speech, the second on how to rectify these faults; the fine illustrations were designed by Abraham van Diepenbeek (1596-1675) who worked with Rubens and made several engravings after works by Rubens. The engravings were executed by Andries Pauli (Pauwels, 1600-1639). Each emblem has a motto and a four-line poem on the opposite page (in Latin).

One of the major qualities of the illustrations lies in their elegant combination of variety and unity. Burgundia selected a broad range of iconographic elements in order to compose an emblem book that has strong thematic unity, while avoiding monotony. For instance, there is a depiction of the memorable bowshot of Geoffrey of Bouillon, King of Jerusalem (II.44), battle of the Pygmies and Cranes (I.11), bottles (I.6), wine barrels (I.9), boxes (I.15), clocks (I.23, II, 7), peddlers (II.18), the killing of a mad dog (II.43), gathering firewood (I.37, II.37), and animals of all description. Burgundia here includes mammals, birds, reptiles, pets, savage beasts, Occidental as well as exotic. The author seemed to especially delight in the use of birds to illustrate "human tongue": the wryneck (or torquil) possesses a free, unbridled tongue (I.1); magpies a garrulous tongue (I.10, I.13); parrots repeat their own name, while toucans boast endlessly (I.16, I.17). Thus, Burgundia's Linguae vitia et remedia functioned as a didactical instrument and ethical guideline in the Low Countries of the seventeenth-century. It provided its readers (young and old) with specific rules for the proper use of speech in daily life; in doing so, Burgundia revived a literary and moral tradition that went far back into classical antiquity.

Rare: Worldcat finds only two copies in the US at the Getty and LOC Rosenwald Collection. A copy of the Dutch edition printed the same year is found at Penn State. This work remained unknown to David Steadman, Abraham van Diepenbeeck: Seventeenth-Century Flemish Painter (1982). A fine copy.

PROVENANCE: The Hoe copy, with his ex-libris in a binding by Trautz-Bauzonnet.

Landwehr, Emblem & Fable Books, 95. Praz p. 292. Hollstein XVII (Pauwels 18). See the introduction to the facsimile edition by T. van Houdt (Turnhout: Brepols, 1999); see also the review by Michael Bath (Emblematica: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies, XII, 2002, pp. 366-371).